On ecclesiastical poetry

When the Blessed Mother saw Christ on the cross, crucified amongst thieves by his own will, she beat her breast and cried: 'Woe is me, my Son! For I hoped as king to see you reigning, whom I see condemned, hanging on the Cross'.

'Gabriel announced, in the wondrous message that he brought me, the eternal kingdom he said would be the possession of my Jesus, my dear Son.'

'Woe, alas for me! Now a prophecy has found fulfilment, as the just man Symeon had foretold, now, Emmanuel, your sword has pierced my heart.'

I would like to preface the text of the Lament of the All-Holy Theotokos with some reflections on ecclesiastical poetry.

There are 'mere words'. They are composed by the intellect and there is way too many of them in print. These drab contrivances of the mind made the spiritual eye hazy and unable to see so many things. These lifeless products of literary factories exhausted the soul. They are moved from one head to another mechanically, as if from a box to a box. It sometimes feels as if the prince of this world, who has all kingdoms in his palm, is also the grand advisor of the world chancellery; he is sorting his bland files into heads like into folders.

These words sometimes lay claim to greatness, but their grandeur is that of paper and fabric flowers, dusty and washed out. Words like this are a mere falsification.

But there are also other words; words in the fullest, highest sense, λογα. They are born of the soul and rip off a part of it whilst born; they bring forth and make known its innermost being. Like golden fruit they grow on the soil of the soul and are ripened by it in due time. The innermost forces of the soul are behind those words, and the fullness of the soul overflows in them. They often appear humble and homely, but they are centres of psychic energy—they are like storm clouds carrying electrical charges. When encountering the soul of another, those powerful words start throwing lightning bolts. Thunders roar in them, and the soul they met is infused with feelings, thoughts and desires it never knew before.

Could it even be any other way? Words like this are written not in ink but in blood slowly dripping from the chest. This blood is life, and it never gets cold or thick.

Powerful words imbued with the Spirit are an unquenchable, lively flame. Just as light is borne from another light, a soul is set ablaze once it is touched by a soul of another that is burning with the Word.

However, the spiritual charge words carry as they affect souls comes from the person speaking those words, from their innermost treasure. 'The good man out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil man out of his evil treasure produces evil; for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks.' (Luke 6:45) The literary word is the most perfect expression of that treasure.

Some words are spells summoning evil powers, but we will not be dealing with those now.

Some words are invocations that carry the mystical song of infinity in them; they bring grace and peace to the one speaking them. As Rufinus of Aquileia tells us in his 'Lives of the Desert Fathers':

There was a holy man by the name of John living there who was imbued with God's grace. He had such a powerful gift of consolation that no matter how much pain someone had to bear, he could bring them joy and peace with just a few words.

Perhaps the words of this abba John were of this kind.

Every person has their own fundamental power and form of innermost, and therefore also outward word. That is what makes the word so valuable. As we read in 'On the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life', commonly attributed to St. Anthony the Great:

Nothing is more precious to man than a spoken word. We bring glory to God with careful words and thanksgiving, yet we're condemning our soul with futile or slanderous words.

Just as there are persons glowing with faith from within, there are words imbued with the Spirit. In a way, such words undergo transubstantiation. 'Under the appearance' of ordinary words, words of a completely different nature are born from the innermost depths of a spirit-bearing person. Those words had the grace of God descend on them. They bring eternal peace and can soothe a sick, exhausted soul. They heal sore wounds. They can sometimes appear homely or awkward, but their slavish gaze beholds Christ and His Mother, and the soul rejoices.

Anyone who understood this transubstantiation of words could see its power with their own eyes. They could see it is possible for ordinary human words to be imbued with His grace when they are spoken by a spirit-bearing person. Is it not like how the cloudy fog of the horizon is pierced with the golden fire of the sunset?

Conversely, in many cases words can be imbued with demonic energy. I will however focus on the first type.

The Holy Scriptures aside, we can find the most of those transubstantiated words in our chants, some of which can appear awkward—and I do not mean plain or unsophisticated. No, ecclesiastical poetry is often very ornate and flowery. You will find them decorated with over-elaborate late Byzantine poetical forms, with acrostics and other artificial rhetorical devices. Yet there is mystical power to be found in those forms, which seem so peculiar to us and were so common for people of that time. The spirit-bearing writers of chants, to whom alone this mystical power pertains, could only write in the same manner as their contemporaries. Yet those words and forms . This aroma will not be caught by a literary critic, but the faithful heart will, no doubt, notice it. The form of the chant is indelible from its spiritual power. Give up the form, and you will also lose all that is so dear to the faithful heart; all that fills it with the bitterly sweet love of missing its Home and Father.

Many are talking about liturgical reforms these days and voicing plenty of interesting opinions. Of course, the spiritual life of the Church can be expressed with liturgical literature. 'The Spirit breaths where He wills'[1], but the Spirit is no subject to committees. He does not concern Himself with job titles or councils. Any attempt to artificially engage with the Spirit inevitably turns liturgical literature into a falsification.

All of this is too easy to be discussed at length. Yet, unfortunately, it is too often forgotten these days when it comes to liturgical reforms. If the Spirit is present, we will have new literature and will not need to ask for it; if not, we will not, no matter how much we ask. Asking just makes us ignore the living tradition we already have without getting anything in return. Do we even need that? Perhaps we have not yet properly understood and appreciated the things we already have? Would it not be better to take a completely different approach, imbuing new words with the Spirit to make sure nothing is unclean?

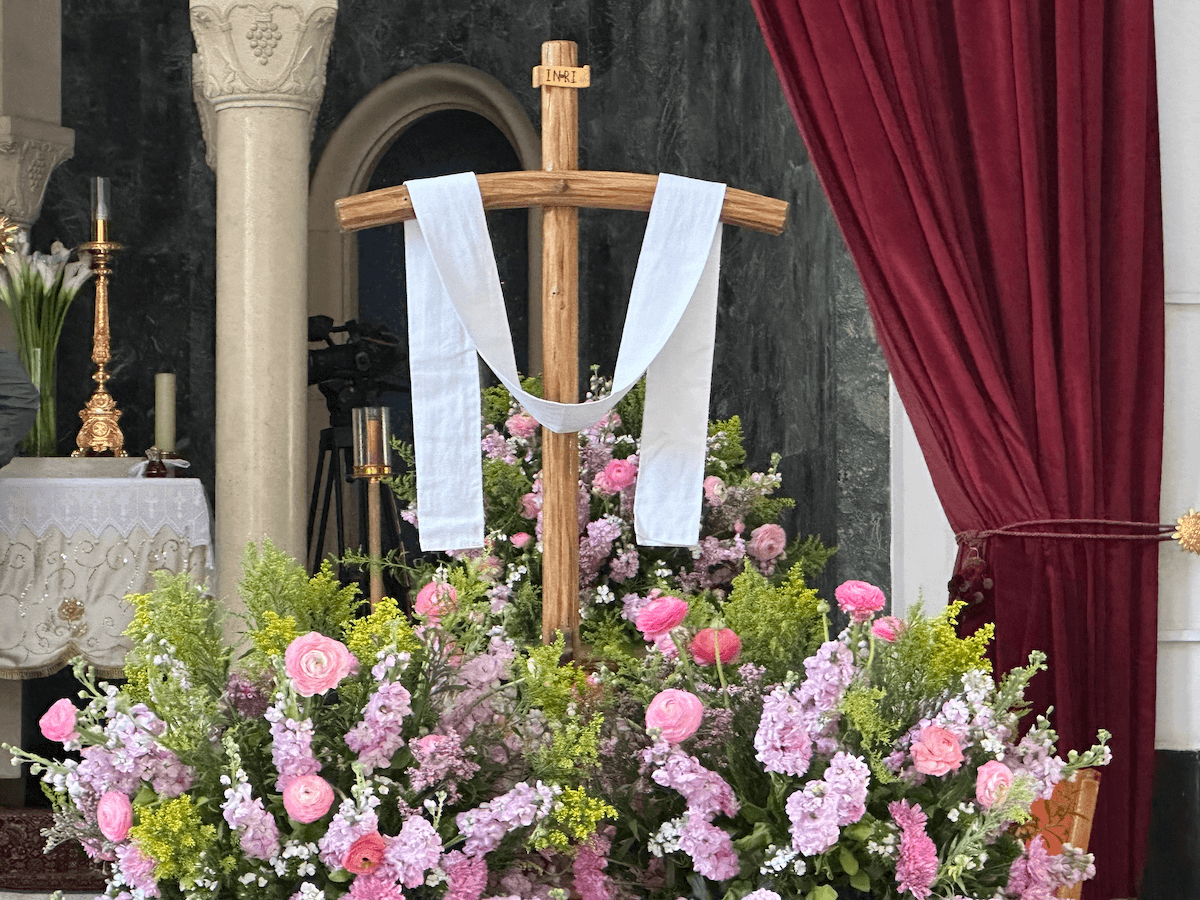

The Church has many majestically powerful chants, but those of the Great Lent and Pentecost in particular shine mysteriously with a distinct spiritual beauty. It is as if the endless depth of His passion and resurrection glows with a mystical light during those services. Other chants include the lesser known work of Symeon the Metaphrast, the Lament of All-Holy Theotokos. It never gained much attention or prominence; supposedly because it is chanted in cells on the vigil of the Good Friday.

When I read it for the very first time, it immediately got close hold of my heart. I think it was only then that I understood the words of the prayer: 'Wound our souls with Thy love'.

Over just a few pages we witness a dreadful tragedy unfold. The Righteous is crucified, God is buried, the Mother is sorrowful and the disciples are despondent. Yet human sorrow and human terror are soothed by His humility and the resurrection which was foretold.

Is there any person who would not be touched by the Lament of the All-Holy Theotokos? I cannot imagine anyone that cold-hearted. But the heart of a man knows neither the pains nor the joys of motherhood; he does not see a part of his own self in his child. His heart will never experience even a thousandth share of the sorrow all mothers will feel whilst reading the Lament. This work of Symeon the Metaphrast is for you, o long-suffering, as you alone can feel it in your hearts and find in it a new source of graceful joy. And you shall one day remind our decadent society about the passions and resurrection of our Lord.

Notes

1. John 3:8, 'the wind blows where it wills'. In Greek, the same word means both 'wind' and 'spirit'. Russian translations of the Bible have traditionally chosen to translate it as 'Spirit', whereas English translations usually opt for 'wind'.