On Pride. Part 1

Last time we talked about humility being what revives and strengthens our faith; it would do us a lot of good to keep talking about humility. Yet therein lies a great difficulty: we have no personal experience of humility. As St. John Climacus says, ‘He who <...> imagines that by his description of things of this kind he will enlighten those who have never actually experienced them, is like a man who by words and comparisons wants to give an idea of the sweetness of honey to people who have never tasted it.’[1] ‘This subject sets a treasure before us as a touchstone, preserved in earthen vessels, that is to say in our bodies, and it is of a quality that baffles all description. This treasure has one inscription which is incomprehensible because it comes from above, and those who try to explain it with words give themselves great and endless trouble. And the inscription runs thus: Holy Humility’[2].

We struggle, almost hopelessly, to talk about humility; which is why I want to talk about pride, something we all know by experience. ‘Pride is denial of God, an invention of the devil’[3], says St. John Climacus.

'The beginning of pride is the consummation of vainglory; the middle is the humiliation of our neighbour, the shameless parade of our labours, complacency in the heart, hatred of exposure; and the end is denial of God’s help, the extolling of one’s own exertions, fiendish character.'[4]

As such, pride eventually leads us to lose our faith. When we are so consumed by vainglory that we are enslaved by it, we reach the middle point of pride. It is still possible to pray at this stage, as evidenced by the Pharisee whose prayer both humiliates his neighbour and praises his own works: 'The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, ‘God, I thank thee that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector' (Luke 18:11). Such a person still prays to God, even though they don't understand just how close they are to losing their faith and denying God's help. Meanwhile the latter, combined with relying on your own strength alone, is the end of pride, 'an invention of the devil'.

Abba Dorotheus identified two forms of pride; they correspond to the beginning and end of pride as described by St. John Climacus.

The first form of pride is when you demean your brother; when you humiliate and revile him as if he was nothing and think yourself superior to him. If you fall into this kind of pride and fail to come to your senses fast enough, you'll eventually end up in the second kind of pride that dares to treat God the same way; you'll believe your accomplishments and good works to be the result of your own intellect and doing, and not God's help.[5]

Abba Dorotheus goes on to tell us about the wretched condition of a brother who was consumed by the first form of pride, also using his example to illustrate how it eventually turns into the second kind.

Indeed, brethren, I knew someone who was once in this wretched condition. At first, should a brother say anything to him, he'd berate him and say: 'And who's that? No one is worthy except Zosima'. He eventually started berating him also and saying instead that nobody is worthy except Macarius. A bit later he started saying: 'Who's Macarius? Nobody's worthy except Basilius and Gregory'. Eventually he started dismissing them as well, saying instead: 'Who's Basilius? Who's Gregory? Nobody's worthy except Peter and Paul'. I said to him: 'Indeed, brother, you will soon start berating them also'. Lo and behold, he soon started saying: 'Who's Peter? Who's Paul? Nobody's worthy except the Holy Trinity'. He eventually felt prideful against God Himself and lost his mind shortly after. This is why, my dear brethren, we must do everything in our power to fight this first form of pride, lest we eventually fall into the second.[6]

Those who want to fight pride should start with fighting its root, which is vainglory. We read in St. John Climacus: 'The only difference between them is such as there is between a child and a man, between wheat and bread; for the one is the beginning and the other the end'[7]. He also refers to vainglory as the 'precursor of pride'[8].

What is vainglory? In its essence, it's a change in our nature and a deviation from the way God created us.

With regard to its form, vainglory is a change of nature, a perversion of character, a note of blame. And with regard to its quality, it is a dissipation of labours, a waste of sweat, a betrayal of treasure, a child of unbelief, the precursor of pride, shipwreck in harbour, an ant on the threshing-floor which, though small, has designs upon all one’s labour and fruit. The ant waits for the gathering of the wheat, and vainglory for the gathering of the riches of virtue; for the one loves to steal and the other to squander.[9]

Whoever labours for God and fails to fight their vanity is also labouring in vain. Their spiritual treasure is being stolen by a thief whose victims could drown not in open sea but right next to the harbour. As the Church Fathers say, 'A vainglorious person is a believing idolater; he apparently honours God, but he wants to please not God but men.'[10] 'Every lover of self-display is vainglorious. The fast of the vainglorious person is without reward and his prayer is futile, because he does both for the praise of men. A vainglorious ascetic is cheated both ways: he exhausts his body, and he gets no reward'[11].

It's important to know how to recognise vainglory in ourselves and what its main signs are. You can tell you're being vainglorious 'when you do something, however trifling, hoping that you will be observed by men'[12]; or 'when a person, seeing no one near him to praise him, puts on affected behaviour'[13].

What is, then, the condition of a vainglorious person? Vainglory enslaves us when we're not fighting it. It poisons every single of our virtues and good works.

The sun shines on all alike, and vainglory beams on all activities. For instance, I am vainglorious when I fast, and when I relax the fast in order to be unnoticed I am again vainglorious over my prudence. When well-dressed I am quite overcome by vainglory, and when I put on poor clothes I am vainglorious again. When I talk I am defeated, and when I am silent I am again defeated by it. However I throw this prickly-pear, a spike stands upright.[14]

We must fight vainglory; we must counteract it with something that could make it go away. Vainglory is an immensely dangerous vice. If we weren't vainglorious, we probably wouldn't do many things; and we can even overcome other vices to indulge in vainglory. So 'vainglory makes quick-tempered people meek before men'[15], yet the reason they restrain themselves is not because that's what the Lord taught and not because they think, 'my brother was created in the image of God that I must not defile'. No, that's because they're scared someone wouldn't think highly of them.

Here is what St. John Climacus tells us:

Once, having become slack, I was sitting in my cell and thinking of leaving it. But some people came to me and began to praise me not a little for my solitary life, and at once the thought of slackness gave place to the thought of vainglory. And I was amazed at how this three-horned demon opposes all the other spirits.[16]

St. John Climacus teaches us here that there's no vice that couldn't be conquered by vainglory. We usually mistake this for a spiritual victory, yet it's a loss, for a weaker vice is simply overpowered by a stronger one instead of being rooted out by repentance and fear of God. Vainglory temporarily keeps this other vice off, conceals it from us and thereby doesn't let us fight it.

When talking about vainglory, we should address the ways it manifests in us. One of them is talkativeness. 'Talkativeness is the throne of vainglory on which it loves to show itself and make a display.'[17] When we indulge in talkativeness, we're indulging in vainglory. Moreover, it's not just about us talking too much; if someone talks to us too much, especially if they're praising us, that also feeds our vanity. 'The silence of Jesus put Pilate to shame, and by a man’s stillness vainglory is vanquished.'[18]

As we can see, we should start fighting pride by first tackling vainglory. There's an efficient remedy for it that God can give us, which is dishonour. 'The Lord often brings the vainglorious to a state of humility through the dishonour that befalls them.'[19]

There are several stages of conquering vainglory. 'The beginning of the conquest of vainglory is the custody of the mouth and love of being dishonoured; the middle stage is a beating back of all known acts of vainglory; and the end (if there is an end to an abyss) consists in trying to behave in the presence of others so that we are humbled without feeling it.'[20]

The beginning is the 'custody of the mouth and love of being dishonoured'. This means I must try to keep my mouth closed and try to understand—as best as I can—that dishonour is good for me. I must humble myself down and tell myself: 'I'm vainglorious, I deserved this'. Vainglorious thoughts will keep attacking us and disturbing us in every work, but we can't start our conquest with them. Every battle against vices starts with actions, not thoughts; I must first learn to keep silent and love dishonour, and only then I can reach the middle stage of conquering vainglory, which is where I'd be preserving my thoughts or warding them away. What is the end, then? It consists in doing things that humiliate us in front of other people without being troubled by it. That's very far from our natural inclinations, and it's the highest imaginable accomplishment. We see it in those who are fools for Christ.

If the limit and rule and characteristic of extreme pride is for a man to feign such virtues as he does not possess for the sake of glory, then it follows that a sign of the deepest humility will be to cheapen ourselves by pretending to have faults that we do not possess. It was in this way that he [abba Simon] behaved who took into his hands bread and cheese. Likewise the exponent of purity who took off his clothes and, free of passion, went through the whole city [venerable Serapion the Sindonite]'[21].

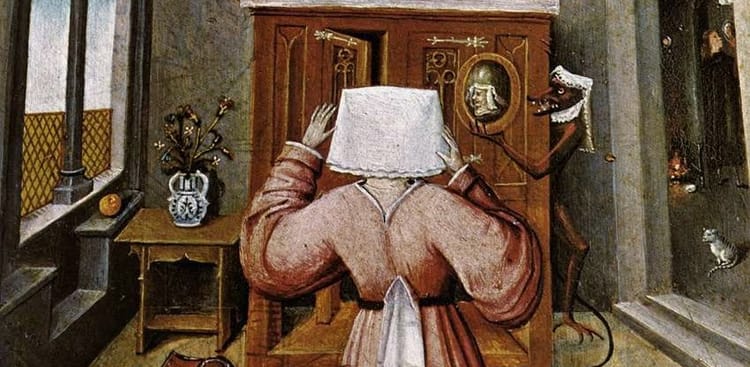

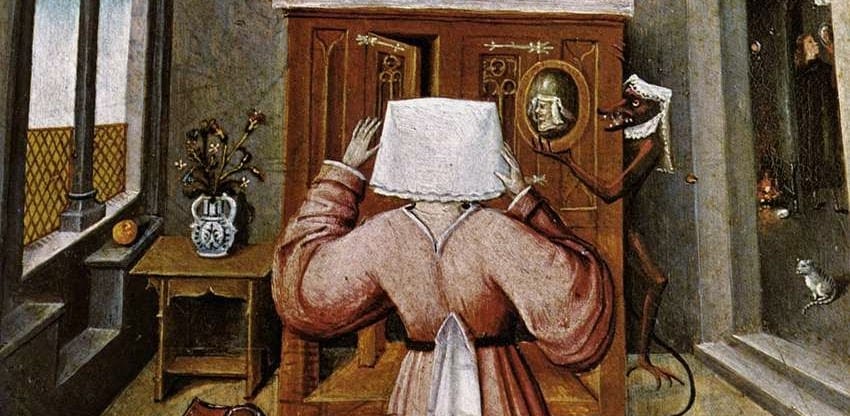

It is the height of vainglory when we delight in ourselves even when we're on our own. For example, an orator would strike a pose thinking about a speech he is to deliver; or an artist would think about a painting to work on and feel as if he'd already done something; or a woman would admire herself in the mirror even when nobody could see her. If so, 'it is certainly a mark of its absence, not to let your thought be beguiled in the presence of those who praise you. If it is a sign of perdition (that is to say, pride) to be arrogant even in poor clothing, then it is a mark of saving humility to have humble thoughts in the midst of high undertakings and achievements.'[22]

Holy Fathers mention other forms of pride as well. Abba Dorotheus says:

There is secular pride and monastic. People with secular pride put themselves above others because they're richer, better looking, better dressed or of a nobler descent than their brother. So when we're feeling vainglorious because our monastery is larger or richer than others, or we have a bigger community, we should realise that's still secular pride. Some people are proud of their natural gifts; for example, some could find pride in having a beautiful voice and being a good singer, or in being skillful and laborious. That's slightly better, but that's still worldly pride. Conversely, monastic pride comes from feeling vainglorious about keeping vigil, fasting or being virtuous. Some even humble themselves seeking glory. All of that falls under monastic pride.[23]

Even though we should seek to fight every kind of pride, we're only human and it's impossible for us to never fall into pride at all. As such, the Fathers say it's better to be proud of your spiritual gifts and not worldly accomplishments: 'If we can't avoid vanity, it's better to be proud of monastic things rather than secular.'[24]

He who is proud of his natural advantages, I mean cleverness, ability to learn, skill in reading, a clear pronunciation, quick understanding and all such gifts received by us without labour, will never obtain the supernatural blessings, because he who is unfaithful in a little is also unfaithful and vainglorious in much.[25]

As if we could fight spiritual pride when we don't even have anything to be proud of! We should however fight secular vanity and remember that whoever is enslaved by worldly pride can't hope for prosperity. We should also remember we must never feel vainglorious about anything, for nothing is ours. All of it is God's gift, for He created us.

It is shameful to be proud of the adornments of others, but utter madness to fancy one deserves God’s gifts. Be exalted only by such merits as you had before your birth. But what you got after your birth, as also birth itself, God gave you. Only those virtues which you have obtained without the co- operation of the mind belong to you, because your mind was given you by God. Only such victories as you have won without the co-operation of the body have been accomplished by your efforts, because the body is not yours but a work of God.[26]

It's hard for us to tell all of those forms of pride apart, so we should start with rooting out vainglory; for it can lead us to deny God's help, which is what the world is doing nowadays. All stages of pride are interconnected. Pride destroys the fruit of any good work, it's a 'shipwreck in harbour', and many vainglorious ascetics only made things twice as worse for themselves. St. John Climacus even says: 'A proud monk has no need of a devil; he has become a devil and enemy to himself.'[27]. If we take all of this to heart, we'll understand what was said at the start: 'The beginning of pride is the consummation of vainglory; the middle is the humiliation of our neighbour, the shameless parade of our labours, complacency in the heart, hatred of exposure; and the end is denial of God’s help, the extolling of one’s own exertions, fiendish character'[28]. We must always remember this, for we are inclined to feel vainglorious about everything we do, everywhere and always.

Let us, then, fight vanity. Let us remember that this battle brings humility, a virtue of which we know nothing and which even St. John Climacus couldn't define: 'Humility is a nameless grace in the soul, its name known only to those who have learned it by experience'[29].

This subject sets a treasure before us as a touchstone, preserved in earthen vessels, that is to say in our bodies, and it is of a quality that baffles all description. This treasure has one inscription which is incomprehensible because it comes from above, and those who try to explain it with words give themselves great and endless trouble. And the inscription runs thus: Holy Humility[30].

References

1. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 25.1.

2. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 25.2.

3. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 23.1.

4. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 23.2.

5. Abba Dorotheus. Instruction 2, on Humility.

6. Abba Dorotheus. Instruction 2, on Humility.

7. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.1.

8. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.2.

9. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.2.

10. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.6.

11. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.7-8.

12. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.36.

13. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 29.10.

14. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.5.

15. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.25.

16. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 27.44.

17. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 11.2.

18. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 11.6.

19. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.38.

20. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.39.

21. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 25.44.

22. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 29.10.

23. Abba Dorotheus. Instruction 2, on Humility.

24. Abba Dorotheus. Instruction 2, on Humility.

25. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 22.31.

26. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 23.16.

27. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 23.31

28. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 23.2.

29. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 25.3.

30. The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 25.2.